The Halloween I was ten, my parents let me go out trick-or-treating by myself. I was a skeleton with a skull-face mask and a costume of bones painted on crisply-ironed cloth. My mother made me wear long underwear, which made me look bulky, with peculiar bulges around the middle where the top tucked into the pants. She wanted me to wear my blue parka as well, but I refused. This was my first store-bought costume, (it came in an orange and black box from People’s Drug), and I was not going to cover it up. I did wear the dark blue hat she offered, however, as it hid my light hair and added to the overall effect. And my father encouraged me by calling it a “skullcap.”

We started in a group: Andy Jenkins, my best friend, who was dressed as Spiderman, Travis Bainbridge and his brother Ray, Brian Heller and Chris Reed.

“Hey, Charlie,” Travis said as I came out. “Neat costume.” I saw with dismay that he was wearing the same one, the mask tilted up on his head, bones partially obscured by a ski jacket.

“Too bad your mom made you wear a coat,” I said in mock sympathy.

“Goddammit!” Travis said, taking it off and tying the sleeves around his waist.

We were systematic about trick-or-treating, going to every house on one side of a street, then down every one on the other. I hated Mrs. Manheimer on Monument Street. She opened her door and stared down at us, a green cardigan sweater draped across her narrow shoulders. “Oh, and what are you supposed to be, dears?” she said, smiling through pursed lips. It was so obvious what we were that I was sure she was going blind.

“She’s probably the one,” said Chris as we left her house. “Better throw hers out.”

“Get out of here, Chris,” Andy protested. “Old ladies aren’t the ones.”

“I’m telling you,” said Chris, shaking his head, “it was the Smarties last year she handed out. I went crazy. I saw purple spiders walking on the wall. It was an acid trip. No doubt about it. I think we should throw hers out.”

“No way,” said Travis. “She gave me a Snickers bar.”

We laughed. I didn’t have anything to worry about. My mother always made me dump my candy on the table when I got home. She threw away anything unwrapped or suspicious, automatically discarding apples and homemade taffy.

“Hey, 319’s giving out peanut butter cups!” yelled a group across the street. We rushed over. Then we told the next group.

“Better watch out for the big kids,” Travis whispered to me, as we ran across the lawn to the next house. “I know this guy, these big kids sprayed him with Nair, and the next day all his hair fell out.” I looked both ways through the eyeholes of my mask.

“It would be kind of cool to be bald,” I said, “don’t you think?” My breath came out in short white bursts. I was cold without my coat, my hands stiff around the string loops of my shopping bag, and I was glad of my hat, but the sense of danger warmed me.

At eight o’clock, the group began to disband, one by one returning home with heavy bags of candy. Their parents had set curfews. Mine had forgotten, had simply trusted that I would come back with the others.

“Come on, Andy, stay out a little longer,” I pleaded, when the others had gone.

“Nah, I can’t Charlie, I’ll get in trouble,” he said. “Come over tomorrow and bring your candy. We can do trades.”

“Okay,” I said, dejectedly. I watched as he dragged off down the street, his paper sack knocking dully against his knees.

It was a dark night, the moon swathed in gray cloud. I was about to go on down Monroe toward home, when I saw a group of big kids coming toward me. They were shouting and laughing loudly, dressed as ghosts and Bowery bums. I recognized Clyde Armstrong, an eighth grade bully, in a pirate’s costume. He saw me, too, and called out. “Hey you! Skeleton! Come on over here, skeleton. I got something for you.”

He had an eye patch over one eye, and a large hoop earring dangling from the opposite ear. He held something behind his back and came towards me. The others followed, whooping and encouraging him.

“Hey, Skeleton, come here,” he said, opening his other hand and showing me the palm. “I’ve got a treat for you.

He beckoned. “Whatsa matter? You scared, faggot? Here’s something for you!” He lobbed an egg. It exploded at my feet. Then he started toward me.

I tore off across the Larsen’s yard and through the leaves, cattycorner to the Brewer’s on Jefferson. I ran up the street a way, then cut through on the other side and came out on a road I’d never been on before. It turned out to be a dead end. I crouched behind a car parked on the street and waited for my heart to stop pounding. No one came after me. I sat down on the curb and ate a Mr. Goodbar from out of my bag.

When I’d regained my breath, I decided that, as long as I was here, I might as well do the street. I looked into my bag, at the glinting wrappers and silver foil. Anyway, it didn’t look quite full enough.

I got two boxes of Milk Duds and a Junior Mints from the first two houses, and a lady with orange hair in the third house gave me some homemade divinity that I ate on the spot so my mother couldn’t throw it out. I sat down for a while and waited for hallucinations, but all I felt was a numbing cold.

The house at the end of the cul-de-sac sat back on a leaf-covered lawn. It was a large brick house with black shutters and a steep porch. Leaves carpeted the porch floor, muffling my footsteps.

I rang the bell and shivered in my thin costume.

The man who answered was large with a red face and a jaw that curved out from his neck like an elephant’s tusk. There were holes in his sweater. He stared down at me curiously.

“Trick-or-Treat,” I said. He opened the door and I stepped into the lighted hallway. He looked like he had no idea what I was doing. I looked expectantly up at him through my mask.

Staring at me from behind his chin, the man looked cross-eyed, almost lost, like he couldn’t see anything past his own enormous jaw. There was music playing softly in the background and the wood smell of a fire. The man continued to stare at me.

“So?” he said finally.

“So?” I repeated. “So, what?”

“So, where’s the trick? Go on, show me your trick, son.”

His stare unnerved me. It was so steady, so intent on waiting. I started to sweat inside my long underwear; my mask felt airless against my face.

“Well?” he said.

“Well, I …” I forced myself from panic by running quickly through my catalog of tricks. It was short. I was going to ask for a deck of cards, when I thought of a trick I could do without one.

“Okay, here,” I said, bringing my arms together in front of my face and very rapidly rotating them around one another until it looked like they were made of rubber.

The man seemed satisfied by this. He nodded vaguely. “Bravo, kid,” he said. He was looking into my bag of candy, which I’d set down on the floor. He bent over and picked out a small cellophane packet of candy corn.

“My favorite,” he said, ripping it open and popping them into his mouth.

“You don’t mind?” he said. One eyebrow rode up on his forehead.

“The dead don’t eat. Maybe you should just leave this for me. You have no use for it.”

I was too shocked to answer. I stared dumbly at the bag between us.

“Jessy,” the man suddenly called into the house. “Come here.

Come look at the skeleton, Jess. The dead are at the door.”

Beyond the hall was a dimly lit room with rows of dark books along the walls. I saw a Raggedy Ann doll lying akimbo on the faded carpet. A little girl with dark circles under her eyes appeared beside the man, peering out at me from behind his knees. She looked about three-years-old.

“See the skeleton, Jessy. Come out and look at him, Jess.” The man moved to one side and put a hand on top of the girl’s head to steer her around him.

The girl hesitated. “l don’t like that skeleton, Papa,” she said, looking frightened.

“Oh, come on, Jess, it’s a nice skeleton. Come rattle its bones.” He beckoned to me. “Come here, kid,” he said, “show Jessy your get-up.”

I took a step forward. She stepped back, her eyes wide with fear. The man reached around and caught her by the shoulder.

“Go ahead, kid,” he said. “Show her. Show her your skeleton moves.”

I made a growling noise and waved my hands wildly. The man laughed.

“Come on, you can do better than that,” he said. He winked at me. “Go on! Scarier!”

I roared louder. The girl shrieked and hid behind the man’s legs. The man laughed again, his jaw tilted towards the ceiling. I saw the pale underside of his neck. I bellowed like a cow and made him laugh harder, waving my arms and doing a stiff-limbed dance.

“Good,” said the man. “Don’t you think, Jess? Try again, kid. Come on. Really scary this time.”

I took a breath and screamed, lunging for the girl with outstretched arms. She started to cry.

“That’s right,” the man said, “that’s convincing. Oh, come on, Jessy, it’s just a boy,” he said. “It’s only a little boy, for Christ’s sake.”

He nudged her forward. “Touch him, Jessy. Go on. What are you scared of, silly girl? It won’t hurt. He’s only a little boy.”

She brought a hand up to her face and held it out slightly. It wavered in the space between us. “I don’t want to, Papa,” she said, bringing her hand down again. “I don’t want to, I don’t want to.”

And she cried harder.

“Oh, come on, Jess,” the man said. His voice was gentle. “It’s nothing to cry about.”

But the little girl couldn’t stop crying; she was holding onto the wall with one hand and the tears kept coming, sliding down her face, drop after drop.

We stood there watching her, the man and I together, with the same detached interest, and I felt oddly close to him for a moment, bound to him in some way against the little girl. From behind my mask, she looked far away, as though she weren’t really little, only viewed from a distance to make her seem small. Her eyes were dull with tears and there were tiny wrinkles along her mouth.

Then a woman’s voice called down from somewhere upstairs. “Jack! Jack! What’s going on down there? Are you all right, Jessy?” The little girl fled up the stairs. The man stared down at me again, his jaw against his chest. He looked as though he might shake me for a second, as though he had caught me as an intruder in his house.

Instead, he held a hand up. “Wait,” he said. He disappeared into the kitchen and came back with a Sugar Daddy in a yellow and red wrapper. I held my bag out, and he dropped it in with a papery thud. “Jess, where are you?” the woman’s voice called.

I looked up and saw the little girl on the landing, staring down at me through the dark wooden balustrade. She had stopped crying and was looking at me with wide, solemn eyes. The stair railing partitioned her small form, breaking it into rectangular pieces of blue dress and dark hair. Her skinny legs were drawn up against her chest. When she saw me looking at her, she shrank back slightly, retreating further up the stairs. I could not see her face then, but I had one last fleeting impression of her staring at me from the shadow, her eyes large with reproach and fear, but fascinated, looking down to see what I’d do next.

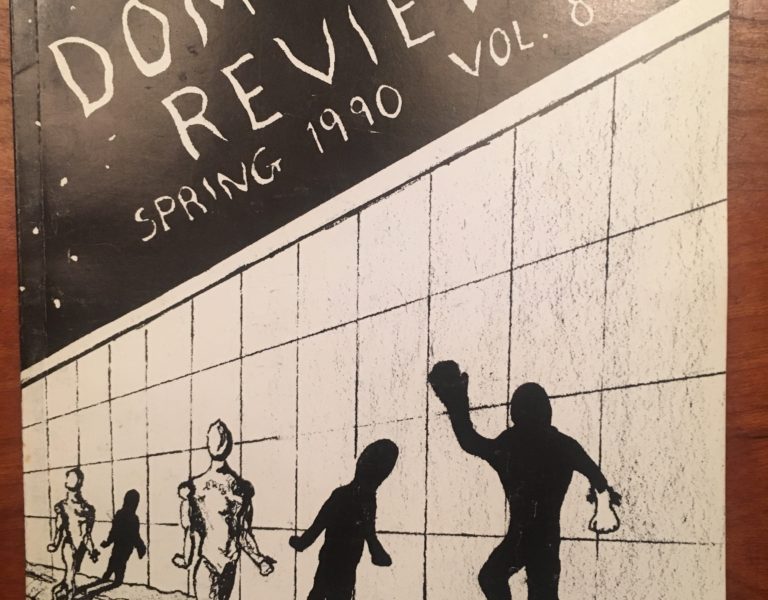

Trick was published in The Dominion Review in Spring 1990.