“Did I ever tell you about the time I ran away to Salt Lake City?” June said, settling back on the couch.

“You ran away to Salt Lake City?” he echoed. His face and voice were eager, urging her forward.

It was the first time June had invited him to her apartment. They had taken the tour; he had admired the photos on her mantel, the watercolor of a New England church, her collection of Depression glass. They had stood awkwardly in her tiny kitchen as she poured wine into mismatched glasses. Now they sat in her living room. He sprawled across her rug like a household pet.

The Salt Lake story flattered June, illuminating a former wildness, a danger; her own detachment showing she’d survived it, managed—just barely—to ensconce herself back within the folds of respectable life. She liked to tell it to men, to see what their reaction would be. It became a kind of test. To see if they valued—as she valued—the rebelliousness of youth, the daring. To find out if they admired her for it. Only it wasn’t true. She’d never gone. Shannon had.

“I was fifteen, ” she said.

Shannon came to her one afternoon and said they were going, she and her stepsister Kit.

“Are you coming with us?” she asked.

They were in her bedroom, Shannon picking at the bedspread, June on the floor with her arms around her knees. She had never really believed they would go. she’d thought it was all talk. Now when she thought of doing it, she felt vertiginous. California is where they would go. Kit’s former boyfriend had an apartment in Carmel. Warm weather. Ocean beaches. Easy money waitressing, lifeguarding.

“We can always turn tricks if we get desperate,” Shannon had said, calmly.

June had pretended not to be shocked.

“Well, will you come?” she pressed now.

Before June could answer. there was a jiggle at the door knob and a flurry of sharp knocks.

“June Hee,” her mother called. “How many times have I told you not to lock this door?”

June rolled her eyes at Shannon and got up to open the door.

“You’re supposed to knock first, Ma, remember?” she said.

Her mother’s round face peered warily into the room. She was wearing a blue velour robe and black slippers. Her glasses were perched atop her graying hair.

“You’ve got something to hide from your mother?” she said, looking around. June turned up her empty palms. “No need to lock yourselves in.”

She started picking up dirty clothes and tossing them into the laundry basket. “Ayoo, Shannon.” June’s mother paused to look at her, her eyes bright as a bird’s. “You’re so thin.” She grimaced, touching her hand to her own cheek. “Want to come downstairs? Have a snack. June?”

“No thanks, Ma.”

“No thanks, Mrs. Shim.” Shannon smiled broadly. “Nice of you to offer.”

June’s mother backed out, nodding. “O.K., O.K.,” she said. “Don’t lock the door, June Hee.”

June got up to lock the door. She could hear the creak of the laundry basket as it was carried down the stairs, the thunk of it against the banister, then the slap-slap of her mother’s heel-less slippers across the vinyl floor. After a short pause there was the hollow metallic clang of the washing machine lid, followed closely by the sound of running water and the rumble of the agitator. The familiarity of the sounds made her want to weep, to scream. She could not imagine her life without them.

She looked across the room, at the desk and bookshelves dense with things she recognized, at her bed with the blue-striped comforter and the nightstand with the clock/radio and the black lamp. There was a crack in the facing wall that resembled a tulip bulb, a stain in the rug beneath her feet where she had once spilled a glass of Coca-Cola. She thought of her father at dinnertime, the clack of his chopsticks on the plate, the strong odor of fermented cabbage on his breath; her mother brought in the soup bowls with two hands, her worried face veiled in steam.

“Well?” Shannon said. June could not read her expression. Shannon was going. June looked at her with envy. Shannon, with her plump, lush breasts; she kissed her boyfriends on the lips and walked around the house in a T-shirt, the dark V of her pubic hair appearing like a shadow below the white cloth. Her gesture of indifference—a hooding of the eyes, slight push of one shoulder toward an ear, blond bangs tossed back against a high forehead—was imperious, regal. June simulated it, but could never get it quite right, the casualness of the pose beneath which there was no real nonchalance, only a surprising intensity, burning with dull heat behind large, appraising eyes. Shannon could run away without concern for her parents’ feelings, without fear of the larger world. June marveled at her cool. When her parents had gotten divorced, Shannon had shrugged. “They should never’ve gotten married in the first place,” she’d said. “It was all just sex.” And when her mother had married again, to a big man with a gray beard and small, woman-like hands, Shannon had made a dismissive gesture and told June, “She’s marrying him for the security; his dick’s a pipecleaner,” leaving June to wonder how she knew.

June was not like Shannon. Physically, she was all flat plain surfaces and acute angles, with her broad cheeks and expansive forehead, her board chest and bony hips. Hers was a physique doomed by the worst elements of her race—the short, rail-like body designed for riding the desert and other Mongol hardships; everything on her face close in, hooded, dark. Emotionally, there was the same economy, something tight in her, encumbered.

It was, perhaps, another racial feature, inbred in Asians, even those born in America—a deeply entangled awareness of family that was far more tenacious than love. Her struggle against her parents seemed the largest part of her. It was what defined her—fighting against their immigrant caution and their work ethic, their displaced values and cultural ignorance. Her father’s hacking cough in the morning, the gravel sound of it a mulish challenge. Her mother’s high-pitched bombardment of worry. June envied Shannon her divorced parents, her sprawling, indifferent stepfamily, her negligent father and silent, unhappy mother. She thought sure she, too, could cultivate the cool freedom of guiltlessness if she had such a family. But all that was inextricable, in June’s mind, with being blond and big-breasted, with cadging cigarettes from older boys and carrying birth control devices around in your purse. It was not so easy when your father demanded every morning if you had changed your underwear, when your mother reached across the table to gouge the sleep from your eyes. Her annoyance at them was vast and deep, but also, somehow, inescapable. They were inside her.

“I’m staying,” she said finally.

“You sure?”

June nodded unhappily.

Shannon shrugged. “Don’t tell them where we’re going then,” she said. “We’re leaving Friday morning.”

“Two of our friends, Mark Edgely and Rabbit Favreau, gave us a ride to the bus station in their van, ” she told him. “We bought tickets to Salt Lake City because I always wanted to see the Salt Lakes. I’d read somewhere about how you could just float around in them. I had a picture of people playing bridge around a floating card table. “

Shannon had cut the picture out of a magazine and given it to her as a memento. The women in the picture wore bathing caps with large rubber flowers on top, their toes peering from the water like tiny periscopes. One of them had on sunglasses with horn rims and long pink fingernails that clutched her fan of cards. “That’ll be us,” Shannon said. She hugged June briefly. “See you,” she said, and then climbed into the van.

Kit was kissing Mark. Her long brown hair entangled them both; his hands had snuck into the back pockets of her jeans. June watched. She had given Shannon a hundred dollars, hastily withdrawn from her account at the First National Bank and Trust, without considering what she would tell her parents. Shannon and Rabbit were making out now in the front seat. June kicked the edge of the curb with an impatient foot.

“Good luck,” she said. “See you.”

The homeroom bell sounded and she ran inside.

“Wow, ” he said, smiling, pleased, as she’d known he would be. “I always wanted to run away from home, but I never had the nerve. “

She shrugged modestly.

“You were only fifteen, ” he said. “I would’ve loved to know you then. ” He looked at her frankly, eyes narrowing in curiosity. “Weren’t you scared?”

She pushed her lower lip out, contemplating. “Scared? ” she said. “Maybe a little. “

It had been horrible. Her parents had gone out to a party, leaving her alone with the television and a frozen pizza.

“We won’t be late,” her mother had said.

“Not past eleven,” her father said. “Yubo, did you give her the number?”

“I wrote it down,” her mother said, waving a pad of paper by the telephone. “Emergency numbers are here, too, June Hee.”

She nodded.

“We’ll lock the door,” her father said. “Don’t open if somebody knocks. Just check through peephole.”

“Then what am I supposed to do?” June asked.

Her father frowned at her, uncertain if she was being insolent. “Call police if someone suspicious,” he said. He pointed. “Number there. Come on, Yubo, we’ll be late!”

She ate the pizza with the television on, her feet up on a chair, wondering where Shannon and Kit were at 6:45, at 7:10, at 8:30. She started in on a bag of pretzels, eating one after the other without pausing. She imagined them on the Greyhound, landscape unfurling before their eyes: the tired mill towns and cities of the region, Schenectady, Burnt Hills, Cohoes, Mechanicsville, Rexford. Then what? She had never been. The flat, uninterrupted span of the Midwest. The nation’s heartland, Mr. Pick, her social studies teacher, called it. She imagined the pulsing heart of some huge, dumb beast. The heart of a cow, an ox. She felt drowsy thinking about bus rides, about cornfields moving backward out the window and the stale smell of closed-in air and urine.

I should have gone, she thought. The first sharp jab of regret. What had seemed incomprehensible was laid clear to her now. This bus ride, this rolling back of scenery, she could see it as vividly as she saw the commercial on television, the blond woman in the red dress getting out of the Lincoln Town Car.

The telephone rang and she answered it. It was Shannon’s mother.

“June?” she said, suspiciously. “Shannon and Kit’ve run away. They left a note, but it doesn’t say where they’ve gone. Do you know anything about it?”

June felt the food in her stomach, a leaden ball. “No,” she said.

“When did you see Shannon last?” Mrs. Franklin asked.

“Umm, Wednesday afternoon,” June answered. “She came over to study after school.”

“And she didn’t say anything to you, about going anywhere?”

“No.”

“June, do you have any idea where they went?”

She thought of the photograph she had of ladies in their bathing caps flourishing in the salt water of Utah; she thought of California dunes and warm winds off the ocean. “No idea,” she said.

“O.K.,” Mrs. Franklin said. Her voice was angry but contained. “Thank you, June. I’d appreciate it if you’d let me know if you hear from them. Good-bye.”

June hung up the phone as though it were something that had died in her hand. She went back and sat in front of the television. She ate the rest of the pretzels and the salt at the bottom of the bag, her mouth and throat turning to dust.

The movie was about an estranged father and son. June hadn’t been following it closely. She wasn’t allowed to watch much television. It fascinated her in the furtive way forbidden objects inspire. She searched for clues—in the replica living rooms of the sitcoms and the rapid-fire commercial images—of some representative American life, some ideal of normalcy she would not have otherwise been privy to.

The movie had reached its climax. The boy and his father were sitting on the front stoop of a small white house, their breath coming out in puffs of smoke as they spoke the first cautious words of their reconciliation. The boy was pale and had dark circles under his eyes; the father was gaunt with skin like cured leather. They stared into the camera instead of at one another, their difficulties manifesting in stammers and trailing sentences.

June watched grimly. The script was trite and the acting bad, but the music swelled and the boy broke down with alacrity. She felt a tightening in her throat, the burn of tears rising in her eyes.

“I love you, Dad,” the boy said. His young face looked humbled, his eyes shiny with hyped-up feeling.

“I love you, son,” said the man, his own face dark with unfathomable emotion.

June began to cry, silently at first, a few unchecked tears sliding from her cheeks. She felt the pressure slowly build, and she moaned once and then started bawling. When she tried to stop, she cried harder. It was as though her heart had become detached from its moorings, like a boat in a storm, crashing inside her ribs with a gale force. Anger flooded her and made her cry more vehemently. Her chest heaved in spasmodic rhythm and the living room was filled with the unrestrained sounds of her keening. Stupid, stupid coward, she kept repeating to herself, begrudging every tear.

June watched the father embrace his son on the nineteen-inch screen, the image comprised of tiny dots of flickering light. The actors held their pose a long time, locked in a stiff tableau of resolution. The words THE END appeared across their heads and forearms. Dumb, June thought, and felt the oppression of her anger. She felt dull-headed and worn, full of mild pollutants that made her sluggish. She was stuck inside a bad story, as though the movie she had just seen were rerunning inside her head. The life she knew, the one she’d clung to, seemed small and untenable.

The credits rolled and still June sniveled on the couch. It was past eleven. She imagined Shannon on the bus, her jacket tucked between the window and her head, trying to sleep through the unsteady lurch of wheels across Midwestern pavement, dreaming of the buoyant waters of the Salt Lakes. It seemed to June that the bus would never stop, that it would keep moving away from her. She felt herself growing smaller and smaller in Shannon’s vision, a fading object in a dissolving landscape.

June heard the sound of a key in the front door lock and wiped her eyes. Her mother came in, unbuttoning her coat, followed closely by her father complaining of something.

“Why, June, what’s the matter?” her mother said. Her bland face registered surprise.

“Why are you crying?”

June felt the surge of grief then. “Shannon ran away,” she bawled, embarrassing herself entirely.

“And how did you get back?” he asked.

“We got picked up at the Salt Lake City bus depot the next afternoon.”

“That was fast!”

“We spent the night in a juvenile detention home and got sent back the next morning.”

His eyes widened. “A juvenile detention home? “

“Yeah. ” She paused. “I’ll never forget it. “

She had ended up telling her parents all about Shannon and Kit’s plan. It had come spilling out with her tears of guilt and grief, and there was momentary comfort in letting it all go. Of course they had made her call Mrs. Franklin right away and comfort quickly ceded to unease.

“Thank you, June. You’ve done the right thing,” Mrs. Franklin had told her, but June was not convinced. She felt like a traitor. Like a prisoner who gives the names of her accomplices without comfort of a torturer.

She hoped that the information she’d given Shannon’s mother would have no effect on the outcome of the search. She imagined Kit and Shannon stopping off at the Grand Canyon, deciding at the last minute to disembark in the Colorado Rockies to snag jobs as cocktail waitresses in Vail or Aspen. She saw Shannon striking up conversation with a guy on the bus, some college-aged smoothie with enticements in Chicago or Memphis. She could feel the rising curve of enthusiasm, the leaning out toward possibility. But Shannon and Kit were found in Salt Lake City the next morning and sent back the day after on another bus.

In school the day they returned, they were regarded as celebrities. The cafeteria crowd gathered around them as they sat on the tables and told and re-told the story of their escape and capture. Little kids rubbernecked from the corners of the room, wide-eyed and open-mouthed at the prospect of such heady freedom. June stayed in the background, avoiding Shannon and Kit as much as possible, keeping her head down as she walked from class to class, counting scuff marks on the gray linoleum. But even so, she couldn’t help hearing versions of their story, in bits and breathless pieces, whispered over lockers and desks, discussed endlessly in the library and at study halls.

“The police came and found them in the bus station,” they said. “Took them to a detention home.”

“Locked them up in separate cells!”

“How’d they know they were in Utah?” someone asked.

“Don’t know,” was the answer.

Waiting for the bus that afternoon June could forestall no longer. Shannon walked over and grabbed her arm. “Let’s walk,” she said. “I’m not allowed to ride home with Rabbit or Mark.” She said the last without rancor, simply accepting the prohibition. They walked a long way without speaking.

June was not going to bring up the subject, and since she could think of no other, she was uncomfortably silent. Their feet shuffled through the dry grass, kicked at roots and loose stones. Shannon walked slightly ahead, in strange-looking sandals with thick soles and suede strips. She wore her customary Indian-print pants, baggy and smocked at the waist, with a sheer, flowing blouse that showed the full curve of her breasts.

“I need a cigarette,” Shannon said, abruptly stopping in the small wooded place by St. Edward’s Catholic Church. Her books cascaded to the ground.

June sat on a tree stump and watched Shannon fumble for a cigarette and matches in the folds of her pocket. Shannon put the cigarette to her mouth and let it dangle from under the thick, almost swollen pink of her upper lip. She struck a match repeatedly against the matchbook with nail-bitten fingers.

“There was a girl in there,” Shannon said. She finally succeeded in lighting the end of the cigarette, took a quick, hard drag and handed it to June. “She was in the next cell over. Screamed all night for a cigarette. ‘Give me back my fucking cigarettes, you bastards!’ she’d yell. And then there would be this noise like she was hurling herself against the metal door. Bam! Bam! Bam!”

“Did anybody come?” June inhaled the hot smoke and held it down inside her lungs.

Shannon shook her head. “Screamed all night,” she said. “And in the morning her voice was like this.” Shannon affected a raspy whisper, “‘You bastards, let me the fuck out of here, you fucking bastards!’”

“Wow,” June said. “Sounds awful.” She exhaled, stifling a cough.

Shannon looked at her a moment and shrugged. “They searched us when we got there,” she said. “Took away our rings and our belts and stuff so we wouldn’t try to commit suicide.”

“Why would they take your rings?” June stared at the rings on Shannon’s fingers, one with snakes, one with a heart, and one with a small diamond.

“You could swallow them, maybe,” Shannon said. “I don’t know. Anyway they took them and put them in a manila envelope. Kit says in her cell there was bloodstains on the floor.”

June contemplated this. She imagined the dark stain on concrete; the smell of the cleanser they would have used to try to scrub it away; the way it would force your eyes to it in the dullness of that small space. What had happened? Some concealed weapon smuggled in? Self-violence, after all, despite the stripping of rings and belts? Or an attempt at murder, one wild-eyed girl against a guard—needing those cigarettes with such ferocity that to be denied them one night was grounds for homocide? June felt she could understand such longing; she felt the heat of violence within herself. The fury of the prisoner, locked in, without rights and privileges, with only the sound of her voice and the solidity of her own pain.

She held her hand out as Shannon again offered the cigarette to her. Smoking gave her a headache, made her feel cloudy and weak. She inhaled deeply and let the nicotine penetrate. Her protected life suddenly nauseated her, the way comfort and routine encased her. She saw herself as she’d been the other night, sitting on the sofa with a bag of Mister Saltys, watching simulated pain on a television screen and sobbing her eyes out. Her own emotions seemed strange to her, simulated themselves, transmitted from some remote broadcast tower. It seemed to June that not going with Shannon had been some sort of crucial failing, a test of character that she had soundly flunked. She could blame it on her parents, on fear or practicality or inertia. But it was not the way she wanted to see herself, wincing and cringing through life from some comfortable remove.

Shannon was staring toward St. Edward’s church. Her face in profile was sharply-sculpted, with a prominent chin and nose that extended the same distance into space. June had never noticed before the delicate, blond hairs on the underside of her neck.

“Shannon?” June said. There was the sound of far-off traffic and a rustling of leaves. She hesitated. Shannon did not move.

“I didn’t tell, Shannon,” June said. “It wasn’t me, I swear.”

Shannon continued staring. The wind picked her hair up and blew it across her face. She looked like a statue, like a brooding, silent statue made of marble.

June ran her hands along the sides of her jeans. She put them in her pockets. “I really wish I’d gone, though,” she said, softly.

Shannon stubbed the cigarette out on the side of the log she was sitting on. It made dusty round marks on the white bark. She collected her books and stood up. “I don’t,” she said. “Wish I’d gone, I mean.” She looked at June then, and her expression was tired. “Really, June, the whole thing was a nightmare.”

“How did they know where to look for you ? ” he asked.

She shrugged. “Rabbit told. He missed Shannon.”

“Was she mad? “

“No. It was just as well, ” she said. “The whole thing was a nightmare.”

She felt it: the stale, claustrophobic air of the Greyhound and the queasy motion; the offending sense of bodies pressed too intimately; the woman across the aisle babbling about a grandchild. Coming into the city early in the morning before the stores had opened and budgeting a cup of coffee and a piece of apple pie at the station restaurant, ignoring the leers from men on benches and the lost expressions of the shuffling homeless. The knockback odor of ammonia smacked her from the floor of the cell she was locked inside. A cot was made up with white sheets and a single gray blanket. Next door a girl screamed for a cigarette, banging against the metal door and calling for the guards.

She wanted to have gone, so much and so hard she wanted, that surely it counted in some way as having been. Over the years her regret at not going had been eclipsed by nostalgia for the vivid images she had of being there. The bus ride, the night in the cell, were more real to her than many of her actual memories. She told herself that Shannon had bequeathed the experience to her, that day walking home from school, which was the last time they had talked about it; she hadn’t seemed to want the memory for her own.

“Did you at least get to see the Salt Lakes before you left? ” he asked.

Startled, June looked at him. Who was he? she wondered, and why had she told him this story? What could it possibly mean to him? But clearly it meant something, because he was sitting up straight on the floor, his eyes alive with interest, buzzing with excitement, as though he, too, had been on that bus, rolling in the dark toward some uncorruptible future.

“The Salt Lakes,” he repeated. “Did you ever get to see them?”

“No,” she said, slowly. “I never have.”

###

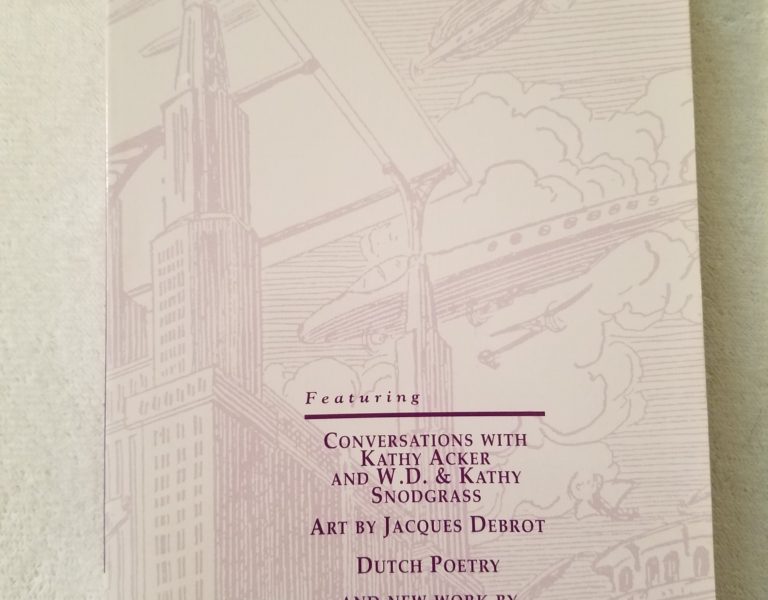

Salt Lake was published in Another Chicago Magazine in Winter/Fall 1995.